Harvesting Children–the Dark Side of Foster Care

By Peter White

About the Book

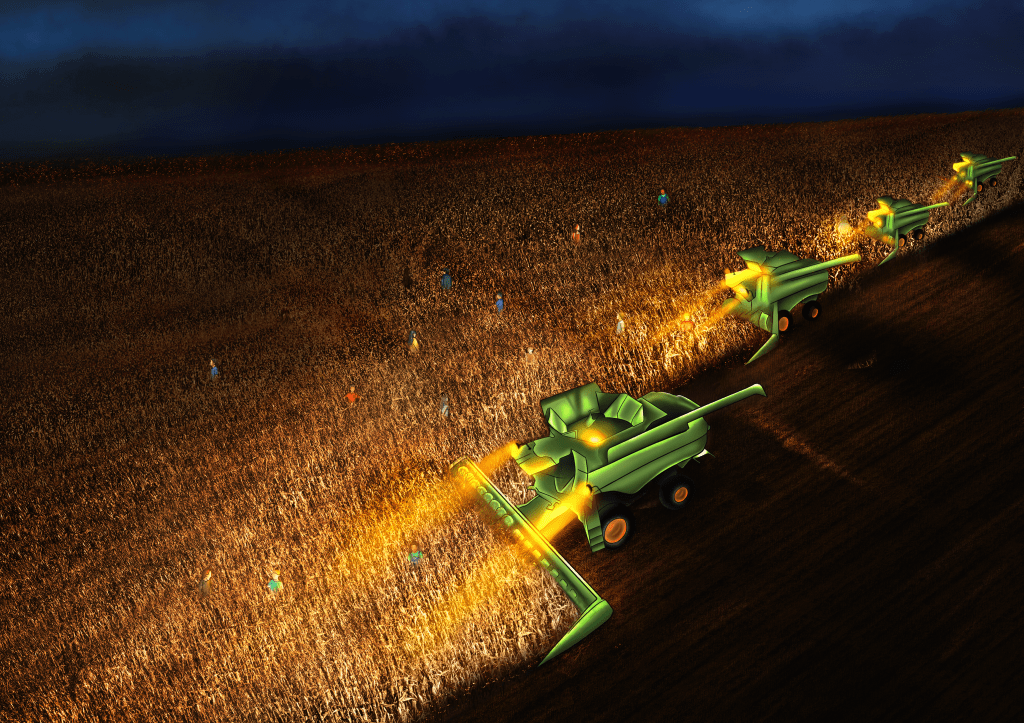

Out of the south, where family, church, and freedom define daily life, a government system created to help children is designed to fail. And fail, it does.

Harvesting Children is about families in crisis and what happened to them after the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services (DCS) wrongfully took their children away. Some parents got their kids back, some didn’t. Either way, everyone was traumatized and their firsthand accounts can be found in this book.

Harvesting Children also examines child welfare agencies in different states. Some agencies are better than others but, still, 600,000 children are taken into custody every year in the U.S. and 400,000 of them are put in foster care. It isn’t just about the children. It is about the grownups, too.

Connie Reguli is a family law attorney who helps parents who sometimes make bad situations even worse. She has battled DCS across Tennessee for 30 years. Crooked officials framed Reguli for a crime they made up and took her law license to keep her from beating them in court so often.

Veteran reporter Peter White describes the elephant in the room that everybody sees but nobody knows what to do about it. Too many kids are put in foster care. This book is about some of them and it explains how they got there.

Harvesting Children – The Dark Side of Foster Care is an exposé of Tennessee’s child welfare system. It examines the roles of its many players and it’s packed with thoroughly researched stories ripped from the headlines. The book also highlights people inside and outside the system who have devoted their lives to changing it. There is an addendum of writings from experts, advocates, lawyers, and scholars you cannot find together in any other place.

This is an invaluable resource for sociology students, parents, grandparents, social workers, judges, lawyers and anybody else who has contact with the child welfare system. The next generation of social workers must be equipped to defend the rights of parents as well as children. They will learn how to do that If they read this book.

What people are saying

“Mr. White eloquently reveals the hidden reality of the public child welfare system that is rarely exposed to the general public. He provides sharp and in-depth tragic examples on how the current system fails families, and, ultimately, society.”

Michael Heard, MSW Social Work Manage Washington State Office of Public Defense

“This is a powerful expose by a seasoned journalist recounting the too numerous stories ripped from the headlines of children and families harmed by state violence unleashed through what is known as America’s “child welfare system.” For more than 50 years, state and local governments have needlessly removed children from their families while profiting by taking billions of federal dollars that encourage breaking up families even when providing direct services is all they need. Read this important book. But be prepared to get very angry as a system that no longer deserves to exist.”

Martin Guggenheim Fiorello LaGuardia Professor of Clinical Law Emeritus New York University

“This book has legs.”

John Köehler, President, Köehler Books.

“This book is filled with horror stories like mine. Unfortunately, they are still doing the same things. I don’t know when it will stop.”

Autumn Moultry, former Tennessee DCS Investigations Supervisor

Outline & Summary

Excerpt

Buy Book

Also Available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Ingram Sparks

Outline & Summaries

Chapter One: Wrongful Taking

This is the book’s scene-setter. It gives 3 snapshots at the top and then describes two cases in detail that show how DCS wrongfully takes children from their families.

One of the book’s main arguments is that DCS takes way too many children into custody and can’t properly take care of the ones it takes. I can’t imagine a more stinging indictment of the ironically-named Department of Children’s Services than the death it served up to little DaCayla Green.

Chapter Two: DCS on the Inside

This chapter begins with 3 snapshots of DCS employees. One of DCS’s major problems is underpaid and overworked caseworkers. Since DCS officials wouldn’t talk to me, I talked to DCS caseworkers and investigators. Throughout the process of reporting about DCS I requested interviews with DCS leadership and second level officials. Never got any. My reporting played a part in ending the tenure of the previous DCS Commissioner, Jennifer Nichols. Her replacement, Margie Quin, hasn’t granted me an interview either.

Chapter Three: How Children Welfare Agencies Operate

This chapter describes DCS operations. It begins with a common universal practice in child welfare cases—unwarranted home searches. Then, it tells about how DCS took Wendy Hancock’s children in Tennessee, how it usually takes children—some people say “kidnaps” them, then how DCS can get you fired from your job, and how Youth & Families Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) rates DCS performance. (poorly) Then I tell the story of a Mom who gave up custody of three kids to get her baby back from DCS custody.

This is one of the book’s longest chapters and has subheads: How Parenting Plans Break the Parent-Child Bond, then a story about a Black Father who fights for custody of his daughter, then Secrets and Lies, then an investigative story called DCS Needs a Major Overhaul.

The Black Dad story has a national context. It describes how much money goes to contractors who provide the bulk of foster homes, academic studies that debunk the myth of drug dependency as a disqualification for parenthood, and the sad outcomes for foster children who age-out of the system.

And it ends with the story of a family who loses a Black child to a white couple who are given custody by a white judge.

Chapter Four: Where Do All Those Kids Go?

They go with relatives or strangers—and are eventually reunited with their birth families about half the time. Some are locked up. This chapter tells the history of the Department of Children’s Services, the Brian A class-action lawsuit in 2001, and several audits by the state comptroller which repeatedly found that DCS failed in its mission to take care of the state’s neediest residents.

The scene is set for the next few chapters with the story of families who came to testify at a legislative hearing but were not allowed to speak. Then the context is widened with two stories from Alabama and Florida that have similar issues.

Chapter Five: Judging the Judges

Chapters 5-8 deal with players who have key roles in Tennessee child welfare. Like anywhere else, they are lawyers, judges, politicians, non-profits, social workers, and family advocates.

Chapter Five features four judges—two good, two bad. This chapter is the heart of the book. It runs 21 pages. It describes how a case moves from when children are first taken into custody through the juvenile court system, and sometimes into higher courts. Like the rest of the book, people are named, what they did is reported, sometimes what they tried to get away with but didn’t, is reported, too.

This chapter tells the story of Family Law Attorney Connie Reguli. She is a foil to both DCS and the judges because she is a family defense attorney. Her role is defending parents and getting their kids back from DCS. In her mind, all the other players are corrupted by a dysfunctional system that unfairly punishes her clients. Reguli’s commentary runs throughout the book but her story comes at the end of Chapter Five because three judges were involved in having her law license revoked.

Chapter Six: Lawmakers and Officials

This chapter is about lawmakers, politics, and welfare officials. It starts with a description of two kinds of Christians and a typical meeting of the House Children and Family Affairs Subcommittee. Then there is a story about the failure to reform the troubled agency.

Then we hear about Gov. Bill Lee, DCS Commissioner Margie Quin, Tennessee Safe Baby Courts and the Strongwell Contract. We hear from Representative Justin Lafferty, a Republican conservative, who says even if DCS had an unlimited amount of cash to spend, it could never substitute for a “loving mother and father in a home to take care of a child”.

Chapter Six ends with a picture of state politics as the 113th General Assembly session concludes in May 2023. Three Democrats took over the microphone, leading to the expulsion of two of them by the Republican supermajority. The incident made national headlines and President Biden met with the “Tennessee Three” at the White House.

This melodrama was about the Lege’s failure to enact gun safety laws and overshadowed the failure of a bill to put a 20-case limit on DCS caseworkers—something that was first proposed in 2017. As one of the renegade representatives noted, their protest was really about how hyper partisanship has prevented their participation in making laws because Republicans simply won’t work with the other side.

I asked the Senate Pro Tempore, Republican Ferrell Haile, if it would be better to even out the number of members from both parties on legislative committees. He shook his head “No” and remarked that there was a long period when Southern Democrats controlled Tennessee and now “they have it coming”.

Chapter Seven: CASA and the Role of NGOs

Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) is a well-known national non-profit that represents children in custody cases. Judges rely on CASA attorneys/advocates to bird dog cases and advise them because they couldn’t possibly do the research for all the families that come into their court.

CASA, like DCS, is seriously conflicted about its mission. Does it represent the child or serve the judge? This chapter has a story that illustrates a common problem when a GAL becomes a tool of the department: neither the child’s best interest nor the court’s impartiality is well-served.

Chapter Eight: Lawyers, Litigators, and How Money Flows through the System

We hear from Jessica Ramsey, a Guardian ad Litem, and Connie Reguli, who we have already met. Reguli is an attorney and family defense activist. Ramsey has her complaints about DCS. In general, she thinks DCS doesn’t act quickly enough to protect children who are at risk. She explains how parents, DCS, the judge, and attorneys each play their parts in a custody case. And she explains about kids who are kept in higher confinement than necessary in order to make more money off of their care.

Reguli tells about her courtroom experiences which led her into advocating for parents and families at a national level. She’s been to Washington at least a dozen times lobbying for changes in federal laws. She talks about her political work, about court-appointed lawyers who push for plea deals instead of fighting for family reunification.

This chapter also includes a critique of for-profit service providers based on a report by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project called The Kids Are Not Alright.

Chapter Nine: Family Defense and Parental Advocates

I decided to add this chapter even though we don’t have these things in Tennessee. In child welfare cases here, parents are guilty until proven innocent. That’s just the way it is. New York, Washington, Colorado, and a few other states get better outcomes because they support parents, families, and children in a less adversarial way. Poor outcomes in Tennessee are due to a number of things. Some of it is politics, some of it is law, some of it is prejudice, some of it is organizational dysfunction, and some of it is rank corruption—but all of it together makes for a dysfunctional child welfare system. Taking a different approach that has proven to work well, suggests that states like Tennessee should adopt it. Child welfare in Tennessee could have a more hopeful future than the dreadful picture I have painted in this book. A brighter future for child welfare in Tennessee is possible but a lot of things would have to change before that happens.

Chapter Ten: Activists and Abolitionists

Community organizers, some academics, and people working inside child welfare agencies are pushing back against the system. They employ different strategies and have begun to move the needle but not very far. The good news is that they know about each other and are calling for fundamental change. It’s too early to say if they will succeed but there has been a call to start organizing a radically different approach to child welfare.

Chapter Eleven: Treating People Like Criminals by Keeping Them in the Dark

This chapter is about the lack of transparency in DCS operations, a very expensive computer system that can’t walk and chew gum at the same time, the unwillingness of successive DCS commissioners to engage reporters, and a comparison between Tennessee and Alabama regarding poverty stats, foster care numbers, removal and placement rates, spending, and where both states fit in the national rankings. This is my most wonky chapter but comes to a simple conclusion: namely, Alabama beats Tennessee at more than just football.

Chapter Twelve: War on Drugs and DCS’s Dirty Little Drug War

Drug use and dependency are much exaggerated by DCS investigators and DCS attorneys. They consider exposure to drugs—even prescribed ones– extreme abuse and most Tennessee judges are convinced that it is. Four stories in Children in Custody are about DCS falsely accusing parents of drug abuse in order to take their kids. A story in Obion County tells about a family whose kids were wrongfully taken, ostensibly for drugs, but the role of a landlord who called DCS on them while they were being evicted, was not disclosed in court.

This chapter has stories about the fentanyl crisis, racial disparity in marijuana arrests, fighting discrimination and drug hysteria, and civil forfeiture. These stories are in stark contrast to how DCS whips up anti-drug hysteria and they support a major premise of this book: child removals are really about punishing parents because they are poor.

Chapter Thirteen: Solutions

This final chapter talks about what Tennessee is doing wrong and what some other states are doing right regarding Child Welfare. And it talks about how too much federal money goes towards foster care and not enough into family support and prevention to keep kids from getting taken. We hear from Richard Wexler, an expert on Child Welfare, who is Executive Director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. Wexler has been the nation’s leading watchdog on child welfare for more than two decades. Connie Reguli describes what she would do if she were in charge of child welfare in Tennessee.

Chapter Fourteen: Addendum: Child Policy Review

This chapter draws on Wexler’s writings on the 2018 Family First Prevention Services Act. Everything else in Harvesting Children is my work product. I have included Wexler’s work because my stories mostly come from Tennessee, Alabama, and Florida and he has a broader scope than my own. I think parents, activists, and academics will find them useful to understand the big picture. My stories detail how these policies fail to protect families and children and what actually happens in child custody cases but I do not have Wexler’s experienced eye about child welfare policy on a national scale. Other articles, resources, and materials about child welfare are included.

Excerpt

Foreword to Harvesting Children-the Dark Side of Foster Care

The stories in this book describe families in crisis and what happened to them. They were originally published in The Tennessee Tribune from August 2021-22. Tennessee’s Department of Children’s Services (DCS) operates a $1.4 billion/yr. child trafficking network and Harvesting Children details the involvement of its many players.

I started investigating the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services (DCS) after an internal survey of DCS employees was leaked to the press. I did a few stories about DCS employees and readers left comments that led to other stories about families. People contacted me via email or left messages at the office. Pretty soon I was overwhelmed with parents and grandparents asking for help. The more stories I wrote the more leads I got but couldn’t keep up with them all.

People were eager to talk. DCS officials were not. Official obstinacy and their unwillingness to answer questions made my investigations difficult and the process changed me. I have become an advocacy journalist for the families and the children caught up in the child welfare system.

I wrote this book to tell their stories, to give them a voice, and to understand how such horrible things happened to them. This book also looks at the child welfare system and the people who run it.

For me it is also a personal exorcism. I lost custody of my kids in a nasty divorce and they grew up with a mother who turned them against me. They are young adults now but the parental alienation they endured is still with them. The anguish of not seeing them grow up is still with me, too. A black father who lost his daughter told me, “You never get over it.” Like the victims in this book, I know what it is like to be caught up in a system that treats people with contempt who come before it seeking justice.

There are two theories about child welfare agencies. Do they rescue neglected and abused children from their deadbeat parents? Or do they run a state security service like a modern-day version of the former East German Stasi? This book takes the latter view. I think in many ways DCS is worse than the ills of abuse and neglect it is supposed to cure.

Academics have studied child welfare to death. Auditors have issued damning reports ad nauseam, and year after year, politicians keep throwing money at child welfare agencies; courts issue consent decrees to force them to improve; nonprofits invest time and money; reporters like me write countless articles chronicling child welfare scandals in the U.S.

This book explains how and why these agencies fail. Politicians, scholars, and welfare officials often claim that family reunification is, or should be, child welfare’s primary goal. But these agencies spend extraordinary amounts of money taking children away from parents and succeed at reuniting them only about half the time.

In Tennessee, most of the $1.4 billion Child Welfare budget goes to pay employee salaries. A second big chunk goes to service providers who have state contracts worth millions. Many are non-profits or church-related.

Tennessee is a deeply red state where churches (11,089) outnumber places that sell liquor by the drink (4,613) by two to one. Whisky and salvation have battled here for 150 years. These days, drugs have been substituted for the demon drink of yesteryear and if you use or fail a drug test, the Department of Children’s Services (DCS) will take your kids away.

According to Richard Wexler, Executive Director of National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, the major problem with child welfare agencies in the U.S. is that they are carceral systems. Like prisons, they rely on hyper-surveillance to wrongfully take children and prosecute parents who are mostly poor.

This view is held by a growing number of researchers, who say Black children are more likely to be removed from their homes and put into foster care than White children. They are also less likely to be reunited with their families. There is a long- standing debate whether this is because of racial bias or because Black families are more likely to be poor and more likely than White families to mistreat their kids.

In any case, the child welfare system has failed to resolve racial disproportionality and disparities for many years. Academics, family advocates, and others are calling for the abolition of child welfare as we know it. I am among them.

The premise behind Harvesting Children is that the state doesn’t parent well and should stop trying to. DCS and its cohorts are not saving abused children as much as punishing their parents. Once kids are put in foster care, the state can start collecting child support from their parents. DCS has custody, so by law they are entitled to it.

DCS caseworkers can’t do a decent job because they have too many cases and too much paperwork. They get reprimanded or fired if they fight too hard for families they are trying to help.

The juvenile court judges who preside over these cases sign emergency removal orders on flimsy or sometimes falsified evidence that provides legal cover for DCS to wrongfully take children from their families before any trial begins.

When most parents go to court, their kids are already gone, and getting them back, if they ever do, is an Orwellian nightmare. The process is rigged and parents navigating the system face a culture of lying that permeates the department from top to bottom.

The bad actors in this book are identified by name and title. They believe anything is better than the severe abuse or neglect kids supposedly are exposed to before the state takes them away. But these cases rarely involve violence, and the “neglect” often is due to poverty.

Families whose children have been taken are lucky to get them back. DCS sues the others to terminate parental rights after 15 months in custody. Under the Social Security Act, the Title IV-E program was created in 1980 as part of the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act. The federal government reimburses states for half the cost of adoptions. For every adoption, states collect a payment. To stop paying these bounties, Congress would have to change the law.

Child welfare has a withering cast of characters who are all invested in a dysfunctional system. This includes lawyers, guardians ad litem, judges, social workers, congregate care operators, foster parents, adoptive families, non-profits, dentists, doctors, therapists, and psychiatrists. These people get involved when the state wants to terminate parental rights.

Family law attorney Connie Reguli describes one such scene in Nashville when she counted seven state functionaries along with the judge and his clerk clustered in the front of the courtroom. Against the phalanx of taxpayer-supported strangers trying to take their children, stood the mother and father and Reguli, their attorney. Three against nine. Doesn’t sound fair, does it? It isn’t.

“It can’t stay the same,” Reguli says. “I have grandchildren, you know? And I know that being vulnerable in the United States does not necessarily mean you have a physical or mental disability. You can be vulnerable if you are a victim of domestic violence, if you are poor, if you are a single mom or a single dad. The bell curve for vulnerability is pretty broad, so vulnerable families are at risk.

As you will discover in this book, Connie Reguli has become one of the leading voices, an outspoken advocate demanding change.

“Change comes not just from a voice but from propelling the message across a broader spectrum,” Reguli told me. She thinks it will take powerful discussions across many segments of American society to transform the child welfare system.

“Social systems in America have changed but until we look at the systemic problems, we can’t effect that change,” she says.

“I mean why is it all going so wrong? All the results are bad from this 1974 law. The results are bad for foster children. The results are bad for families. The results are bad financially. The results are all bad. We know that. So, we need a change but until we look at the systemic categories of problems we can’t effect that change,” Reguli says.

“We have to understand that the system is broken and the problems are systemic. These stories are not purely academic. One family is affected here and one family is affected there. But these stories are repeated over and over and over in every community and every state. They reveal problems that are affecting families all across the country.”

Child welfare authorities in the U.S. are removing staggering numbers of children just like church and civil authorities did a century ago with American Indian children and like Canadians did with their First Nation children. The rationale was as bogus then as it is now.

The reason so many kids get taken is because their families don’t have the money to defend themselves with a good lawyer. They aren’t middle class like the people who are prosecuting them or the people who rush to stereotype impoverished parents as sick or evil and, therefore, should have their children taken from them.

But once taken, most do not thrive in foster care. Being a foster child can be like playing a demented game of musical chairs. In 2021, DCS moved 1,612 children once, 818 twice, and 740 children three or more times. Many of them become maladjusted adults who are psychologically disturbed and end up in prison once they age-out of the system.

Compared to their peers, foster kids are seven times more likely to experience depression, six times more likely to exhibit behavioral problems, and five times more likely to feel anxiety.

Researchers have investigated every aspect of child welfare to find out what is wrong and why it is so bad. The best answer policy wonks can offer is that various unnamed sources “lack the political will” to “do what should be done”, by which they usually mean, enact major reform and stop throwing even more money into policing families.

We are always hearing that there aren’t enough foster parents, group homes, and adoptive homes to house all the kids DCS takes. The solution is quite simple: stop taking so many kids into custody, provide wraparound services to families, and return the kids to their parents quickly. In the Volunteer State, none of those things is happening with any consistency.

The $1.4 billion DCS budget should be redirected so families get the social services they need. DCS offers services to families it controls but uses a carrot and stick

approach that is cruel and ineffective. Imagine how ambivalent parents must feel when DCS offers help while simultaneously trying to take their children away forever.

What DCS says it does is often at odds with what it actually does. DCS is hopelessly conflicted about its core mission: should it be reunifying families or should it be getting as many children adopted as quickly as it can? Most, if not all, child welfare agencies in the U.S. are similarly conflicted.

Two things have become abundantly clear: children who spend too much time in custody are not served well and most state agencies that manage foster care have been failing to do it well for the last 60 years. Of course, some are better than others. There are a handful of states using a holistic and multidisciplinary approach that lessens the time spent in foster care and increases family reunifications.

However, it’s doubtful things will change any time soon in Tennessee. The department should be dismantled and rebuilt from the ground up with completely different leadership. The last two DCS Commissioners spent years in the criminal justice system but not a single day as social workers. A good system should be transparent, which DCS is not, and it needs to stop punishing parents by devoting itself to helping families stay together.

I would like to thank Connie Reguli, Richard Wexler, Maleeka Jihad, aka MJ, Melaniia Jordan, Michael Heard, and activist Joyce McMillan for educating me about child welfare. Their experience and insights are present throughout these pages. Judge Sheila Calloway and Magistrate Mike O’Neil and Juvenile Court Clerk Lonnell Matthews helped me understand the role of juvenile courts in child welfare cases. Jessica Ramsey provided invaluable insight about Guardians ad Litem and Senator Ferrell Haile described baby courts, one good thing that is actually helping drug- addicted mothers turn their lives around in Tennessee. Brian Narelle titled the book. I would especially like to thank my editor, Robin Goodrow, who convinced me to share my own story. I am also in debt to the dozens of caseworkers, advocates, officials, non-profits, and families who told me their stories. I hope I have told them well and true.

Peter White

Kingston Springs, Tennessee May 1, 2025